| |||||

| |||||

Unless correspondents ask us not to, this Website will post selected letters that it receives and invite open debate. |

Michael Tang of Hong Kong asks, Monday, October 27, 2003, for our opinions on three historians

Ian Kershaw, Richard "Skunky" Evans, Peter Padfield --

WHAT'S

your opinion on their works? Personally I find Ian

Kershaw to be the better one, though he's a bit lazy on

doing any primary research, and is just profiting from the

efforts of others and the halo of his less than justified

reputation in historiography.

WHAT'S

your opinion on their works? Personally I find Ian

Kershaw to be the better one, though he's a bit lazy on

doing any primary research, and is just profiting from the

efforts of others and the halo of his less than justified

reputation in historiography.

As for Richard Evans, I have read his In Hitler's Shadow, a piece of total crappy anti-German propaganda that's not even worth the paper printed on.

But Peter Padfield must rank as one of the lowliest scums in publishing. All his biographies of Himmler, Dönitz or Hess are rubbish -- shoddily written and researched, though dressed up as serious historiographical studies through the listing of original sources like KTBs [war diaries] (he even claimed the SA was a Freikorps!)

![]()

Our

dossier on Sir

Ian Kershaw

Our

dossier on Sir

Ian Kershaw Our

dossier on Richard

"Skunky" Evans

Our

dossier on Richard

"Skunky" Evans Our dossier on

Heinrich Himmler

Our dossier on

Heinrich Himmler Sir

Ian Kershaw reviews Prof Richard Evans' book Telling

Lies about Hitler

Sir

Ian Kershaw reviews Prof Richard Evans' book Telling

Lies about Hitler The

Sunday Times scornful of Evans's latest product

The

Sunday Times scornful of Evans's latest product

Bookmark

the download page to find the latest new free

books

David Irving responds:

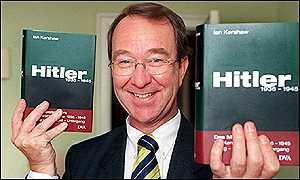

I HAVE no opinion of Sir Ian Kershaw other than assigning him the Pinnochio icon on this website; I invited him to appear as an expert witness in the 2000 trial of Deborah Lipstadt's libels. He ducked out, apologizing in a letter that his knowledge of the German language was not up to it.

That may be true, but I think it was lack of moral fiber. He knew what he could expect if he stood up for Real History against the moneyed onslaught of the defendants. Just see what happened to the conformist historians Sir John Keegan and Professor Donald Watt who spoke up after the trial in my favour, although (to protect them) I had had to force them into the witness stand with sub-poenas.

If Kershaw (below) lacks those two qualities -- German language skills and the courage of his convictions -- what does that say about his worth as a Hitler historian?

MY VIEWS on Richard Evans are well known. This mediocre, venal Marxist academic has earned his nickname The Skunk. Giving his "neutral" evidence at the Lipstadt trial (for which the defendants paid him a quarter of a million pounds), he squirted bile on the reputations of the world's most justifiably famous and gifted historians because they had spoken well of my works for forty years -- he called them negligent and ignorant.

Gradually however his noisome reputation is being spoken of more widely. Yesterday in The Sunday Times Michael Burleigh trashed Evans' latest book, the first volume of a million-pound three-part trilogy on the history of the Third Reich, on which Evans must have worked for, oh, at least a year since the trial.

Burleigh knows how to wield a pen: he refers to "the desire of tenured radicals to display their 'anti-fascist' credentials to a world still relatively ignorant to the crimes of Marxists." No prizes for guessing whom Burleigh is referring to here. But there is more, as the reviewer detects The Skunk's habit of pissing on his more able rivals: O-Ton Burleigh:

"With weary curiosity one turns to the first instalment of Richard J Evans's trilogy on the Nazis. While the introduction is heavy on details of the author's career and querulous wiggings for competitors, it offers a few clues as to why a scholar of Evans's calibre should produce three tomes on this subject, though cynics might think of some answers."Burleigh then refers again to "the author's evident sympathies for the Marxist opposition, [which] lead to a caricature of doughty leftists being beaten up or

killed by sweaty, beer-swilling thugs while the rest of the population has vanished." Finally he puts the boot in to this unappetising Cambridge University department head, writing that Evans "is convincing, too, on the jiggery-pokery in German academia once such characters as Heidegger gained power, but then most people know what academics are like." Ouch.

I NOW come to the strange case of biographer Peter Padfield. I had never heard of him when Adam Sisman, my then editor at Macmillan UK Ltd, who were my publishers too, approached me back in the mid 1980s with a problem. They had perhaps foolishly commissioned a biography of Heinrich Himmler from Padfield, who had previously written on Grand Admiral Dönitz. The manuscript had now arrived and, ahem … 'nuff said.

In short, Macmillan's asked me to report on the manuscript -- a rather unusual move, with a published author like Padfield.

Reporting on a manuscript is a task I have rarely agreed to, as it brings all ones personal prejudices to the fore; invited once to write a report on the Reinhard Heydrich biography submitted by a Swiss historian of some notoriety, well-known for his over-political approach to themes like the Reichstag Fire, I had turned the job down and explained quite simply I did not feel I could report fairly. (Macmillan rejected the book for other reasons).

As I had never heard of Padfield, nor was I then writing on Himmler, I felt I could be objective. A fee of £200 was agreed for my report. What should have been a two-day task eventually took three or four weeks, and I produced a 200-page typescript report on the Padfield manuscript, highlighting its failings.

Despite a lengthy bibliography, Padfield had mostly relied on a dozen source books and had done no archive work at all: Evans would probably warmly approve of him. It is always possible to write a useful thirteenth book in such circumstances (not that I have done so), but it depends on picking the right twelve books to lean upon.

I identified at once the book Conversations with Hitler, by Hermann Rauschning: published in 1940 by the Hungarian-born Jewish wartime propagandist Imre Revesz (Emery Reeves) the book led to furious secret investigations by the top Nazis who established that Rauschning had spoken with Hitler but once, and briefly, at a diplomatic cocktail party. Like the part-fake Ciano diaries, the Rauschning book is one of the favourite source books of lazier historians.

Another work used by Padfield was The Kersten Diaries. Now, Felix Kersten -- Himmler's physician -- did write real diaries, and there are other useful documentary sources on him; but the published book is not the real diaries. (Compare the chapter he wrote on the "Hitler medical dossier" which he claimed Himmler had once shown him, with Hitler's actual medical dossier, which I found in the US National Archives and published in 1983).

And of course, Padfield used the published Walter Schellenberg memoirs (London, André Deutsch): but compare it with the original handwritten memoirs (now in the Institut für Zeitgeschichte), and his voluminous interrogations (Public Record office, London), and you will see that the Deutsch book is less by the SS Intelligence chief than by Mr Deutsch himself.

I could go on, about each of the other source-books used by Padfield. As a bonne-bouche I put into my report a few of the original Himmler documents which I had obtained over the years, to show the kind of book which in my view Padfield should and could have written.

THOSE were, unfortunately, weeks of flux at Macmillan's. A new CEO had been appointed, Felicity Rubinstein of the famous and gifted literary/legal Rubinstein family. She was 23. Many of the top editors resigned in outrage, among them -- to my regret -- my own editor Adam Sisman.

He was replaced as editor by the spineless Roland Philipps; Philipps came under outside pressure a few years later, and on July 6, 1992 he secretly ordered that all of my books were to be destroyed within 24 hours and that I was not to be informed of this and that there was to be "no publicity". Ms Rubinstein's views on this are not known. Philipps subsequently married Ms Rubinstein, which must have insulated him from criticism, but he moved to Hodder & Stoughton, another old publisher of mine, in January 1994.

All of this had little directly to do with the publishing of Real History. I gave up writing my analysis on Padfield's book after churning through three-quarters of it, writing in the covering letter to my report that there was little point my continuing, as they would no doubt not be publishing the manuscript in the circumstances.

To my considerable surprise the book did appear later that year; it contained passages which bore a flattering, if remarkable, similarity to parts of the 200 page report I had submitted. As for the fee, I never saw it.